How to land an aircraft

A good landing begins with a good approach (see below). Before the final approach is begun, the pilot performs a landing checklist to ensure that critical items such as fuel flow, landing gear down, and carburettor heat on are not forgotten. Flaps are used for most landings because they permit a lower- approach speed and a steeper angle of descent. This gives the pilot a better view of the landing area. The airspeed and rate of descent are stabilized, and the airplane is aligned with the runway centreline as the final approach is begun.

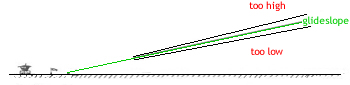

An important element that is learned by the student pilot 'by just keeping on doing it', is to maintain the right attitude and rate of descent during the approach. Gradually one learns to 'see the picture'..... of how much nose cowling can be seen, and the perspective of the runway. It can be difficult at first if you are landing on different sized runways, as one must make a mental adjustment to the 'picture'. The numbers on the runway are an important pointer whether you are going to overshoot or land short.

If the numbers start to disappear under the aircraft's nose, you are landing long.

If the number distance themselves from the aircraft's nose, you are landing short.

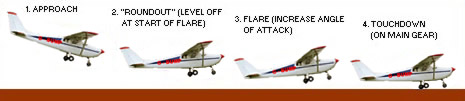

When the airplane descends across the approach end (threshold) of the runway, power is reduced further (probably to idle). At this time, the pilot slows the rate of descent and airspeed by progressively applying more back pressure to the control wheel. The airplane is kept aligned with the centre of the runway mainly by use of the rudder.

Continuing back pressure on the control wheel, as the airplane enters ground effect and gets closer and closer to the runway, further slows its forward speed and rate of descent. The pilot's objective is to keep the airplane safely flying just a few inches above the runway's surface until it loses flying speed. In this condition, the airplane's main wheels will either "squeak on" or strike the runway with a gentle bump. With the wheels of the main landing gear firmly on the runway, the pilot applies more and more back pressure on the control wheel. This holds the airplane in a nose-high attitude which keeps the nose wheel from touching the runway until forward speed is much slower. The purpose here is to avoid overstressing and damaging the nose gear when the nosewheel touches down on the runway. The landing is a transition from flying to taxiing. It demands more judgment and technique than any other manoeuvre. More accidents occur during the landing phase than any other phase of flying. Fortunately, most of these accidents bend the aircraft rather than people. Variables such as cross wind, wind shear and up-and-down draft add to the problem of landing. Good pilots can be easily recognized. They land smoothly on the main wheels in the centre of the runway and maintain positive directional control as the airplane slows to taxiing speed.